By: Scott Orsey

Change is hard, especially where structure creates imbalance in perspectives, power and impact. When years of good intentions yield underwhelming results for children and families, it is time to question the approach. In this four-part blog series, Scott Orsey explores the model used by scientists to measure health and well-being. He arrives at three conditions for change. Might these be the building blocks for the transformation we seek?

I am fascinated by the mathematical models people build to simulate activity observed in the real world. Models, of course, are imperfect. They can only approximate underlying behaviors, and they can have biases or be incomplete. They are built from observation, and can, at best, only emulate universal truths. However, even with these modeling limitations, once a system is expressed in mathematical terms, then the math itself can uncover ever more implications about what is happening in the world. Derived conclusions can be tested against observations and logic. I’ve written previously about one of the most famous physical-world predictions of mathematics that took a century to prove in my article on measurement challenges and Einstein’s “gravitational waves.” It is profound that math can give so much insight.

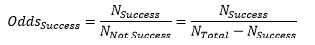

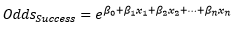

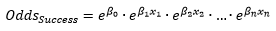

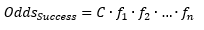

Unfortunately, there are few “first principles” equivalents to Einstein’s Theory of Relativity in the health and social services work that so many of us engage in to strengthen children and families. We don’t have fundamental E = mc2 types of understanding of human behavior and health. It is far harder to build sophisticated deterministic models (admittedly, physicists have also learned that even our universe is not as deterministic as we once thought). Instead, we model results using probability and we test the likelihood that our hypotheses about what works are true. In so doing, we seek to tease out the influence of a whole host of factors related to our desired outcomes.

I wonder if looking at the mathematical models we use to predict outcomes and evaluate our programs could provide deeper insights into the nature of our work and derive the conditions for our success.

In this blog article, I will frame a common mathematical model in what I hope to be a simple, easy-to-understand form. In future articles in this series, I plan to use that formulation to draw implications for our work. I hope in doing so, we might glean answers to some challenging questions. For example, what must we do to have the impact on children and families that we desire? How do we relate to the other people and organizations working in our communities? Why haven’t we made more progress against our goals than we would like? How can those with power and influence help improve the outcomes for all?